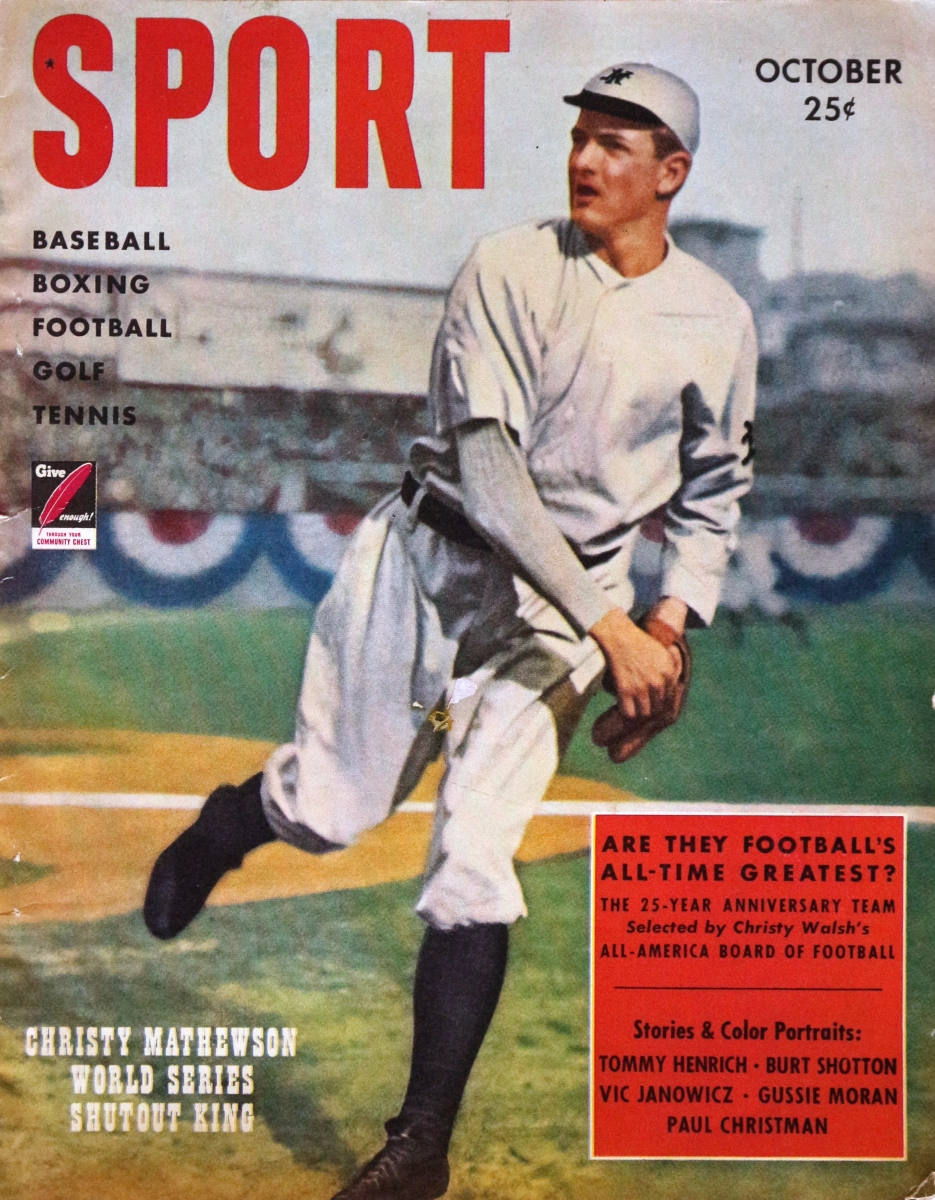

Sport Magazine - October, 1949

Interesting note: On the title page, the small photo of a ball player (identified as Joe Jackson) is actually his White Sox teammate, Buck Weaver!

THIS IS THE TRUTH!

Just 30 years ago this month, the infamous World Series between the Chicago White Sox and Cincinnati Reds took place. The leading figure in the great scandal that followed, the famous White Sox slugger of 1919, tells in his own words his side of the story

By SHOELESS JOE JACKSON

AS TOLD TO FURMAN BISHER

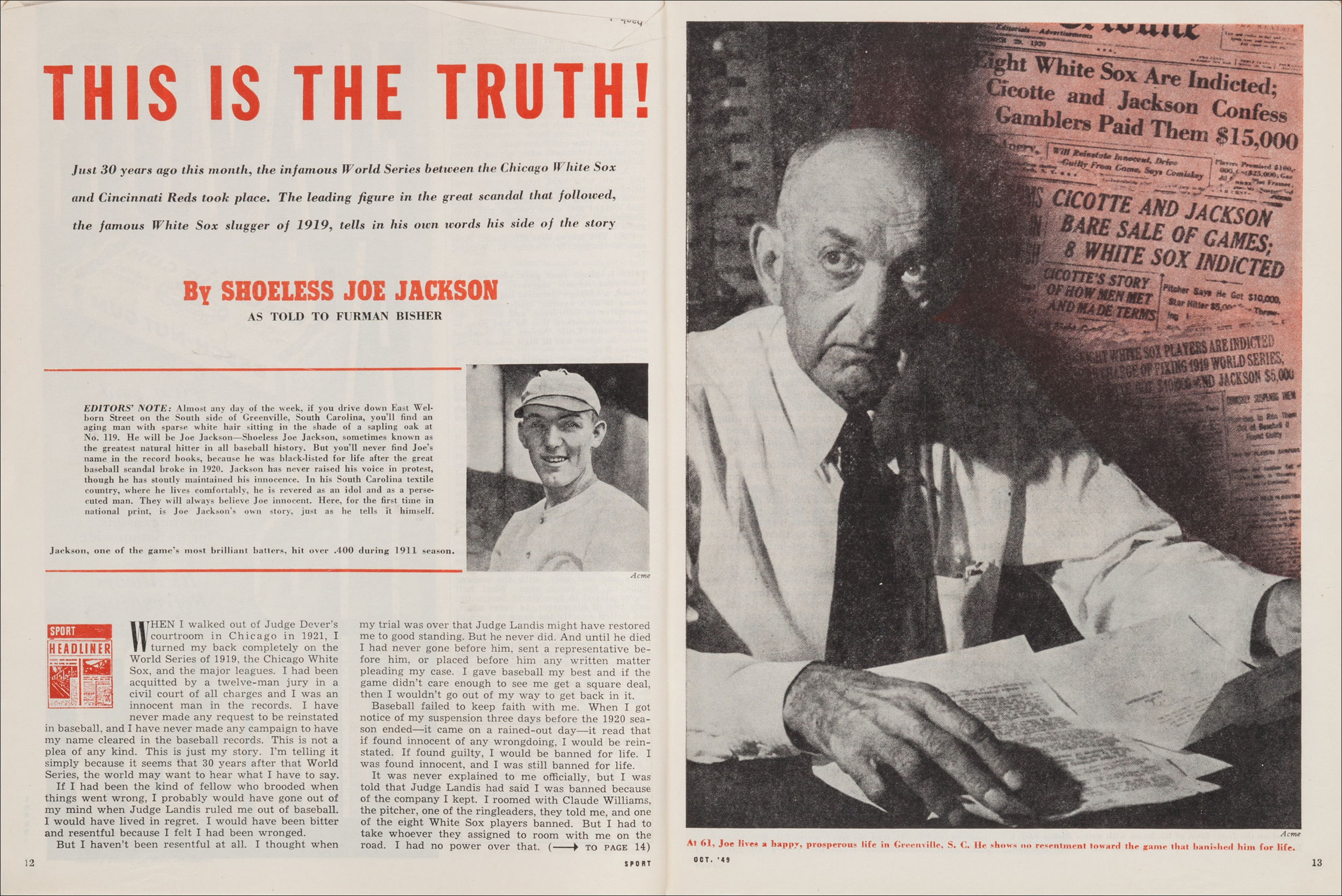

EDITORS’ NOTE: Almost any day of the week, if you drive down East Welborn Street on the South side of Greenville, South Carolina, you’ll find an aging man with sparse white hair sitting in the shade of a sapling oak at No. 119. He will be Joe Jackson – Shoeless Joe Jackson, sometimes known as the greatest natural hitter in all baseball history. But you’ll never find Joe’s name in the record books, because he was black-listed for life after the great baseball scandal broke in 1920. Jackson has never raised his voice in protest, though he has stoutly maintained his innocence. In his South Carolina textile country, where he lives comfortably, he is revered as an idol and as a persecuted man. They will always believe Joe innocent. Here, for the first time in national print, is Joe Jackson’s own story, just as he tells it himself.

When I walked out of Judge Dever’s courtroom in Chicago in 1921, I turned my back completely on the World Series of 1919, the Chicago White Sox, and the major leagues. I had been acquitted by a twelve-man jury in a civil court of all charges and I was an innocent man in the records. I have never made any request to be reinstated in baseball, and I have never made any campaign to have my name cleared in the baseball records. This is not a plea of any kind. This is just my story. I’m telling it simply because it seems that 30 years after that World Series, the world may want to hear what I have to say.

If I had been the kind of fellow who brooded when things went wrong, I probably would have gone out of my mind when Judge Landis ruled me out of baseball. I would have lived in regret. I would have been bitter and resentful because I felt I had been wronged.

But I haven’t been resentful at all. I thought when my trial was over that Judge Landis might have restored me to good standing. But he never did. And until he died I had never gone before him, sent a representative before him, or placed before him any written matter pleading my case. I gave baseball my best and if the game didn’t care enough to see me get a square deal, then I wouldn’t go out of my way to get back in it.

Baseball failed to keep faith with me. When I got notice of my suspension three days before the 1920 season ended – it came on a rained-out day – it read that if found innocent of any wrongdoing, I would be reinstated. If found guilty, I would be banned for life. I was found innocent, and I was still banned for life.

It was never explained to me officially, but I was told that Judge Landis had said I was banned because of the company I kept. I roomed with Claude Williams, the pitcher, on of the ringleaders, they told me, and one of the eight White Sox players banned. But I had to take whoever they assigned to room with me on the road. I had no power over that.

Sure, I’d heard talk that there was something going on. I even had a fellow come to me one day and proposition me. It was on the 16th floor of a hotel and there were four other people there, two men and their wives. I told him:

“Why you cheap so-and-so! Either me or you – one of us is going out that window.”

I started for him, but he ran out the door and I never saw him again. Those four people offered their testimony at my trial. Oh, there was so much talk those days, but I didn’t know anything was going on.

When the talk got so bad just before the World Series with Cincinnati, I went to Mr. Charles Comiskey’s room the night before the Series started and asked him to keep me out of the line-up. Mr. Comiskey was the owner of the White Sox. He refused, and I begged him: “Tell the newspapers you just suspended me for being drunk, or anything, but leave me out of the Series and then there can be no question.”

Hugh Fullerton, the oldtime New York sportswriter who’s dead now, was in the room and heard the whole thing. He offered to testify for me at my trial later, and he came all the way out to Chicago to do it.

I went out and played my heart out against Cincinnati. I set a record that still stands for the most hits in a Series, though it has been tied, I think. I made 13 hits, but after all the trouble came out they took one away from me. Maurice Rath went over in the hole and knocked down a hot grounder, but he couldn’t make a throw on it. They scored it as a hit then, but changed it later.

I led both teams in hitting with .375. I hit the only home run of the Series, off Hod Eller in the last game. I came all the way home from first on a single and scored the winning run in that 5-4 game. I handled 30 balls in the outfield and never made an error or allowed a man to take an extra base. I threw out five men at home and could have had three others, if bad cutoffs hadn’t been made. One of them was in the second game Eddie Cicotte lost, when he made two errors in one inning. One of the errors was on a throw I made trying to cut off a run. He deflected the ball to the grandstand and the run came in.

That’s my record in the Series, and I was responsible only for Joe Jackson. I positively can’t say that I recall anything out of the way in the Series. I mean, anything that might have turned the tide. There was just one thing that doesn’t seem quite right, now that I think back over it. Cicotte seemed to let up on a pitch to Pat Duncan, and Pat hit it over my head. Duncan didn’t have enough power to hit the ball that far, particularly if Cicotte had been bearing down.

Williams was a great control pitcher and they made a lot of fuss over him walking a few men. Swede Risberg missed the bag on a double-play ball at second and they made a lot out of that. But those are things that might happen to anybody. You just can’t say out and out that that was shady baseball.

There were supposed to have been a lot of big gamblers and boxers and shady characters mixed up in it. Well, I wouldn’t have recognized Abe Attell if he’d been sitting next to me. Or Arnold Rothstein, either. Rothstein told them on the witness stand that he might know me if he saw me in a baseball uniform, but not in street clothes.

I guess the biggest joke of all was that story that got out about “Say it ain’t so, Joe.” Charley Owens of the Chicago Daily News was responsible for that, but there wasn’t a bit of truth in it. It was supposed to have happened the day I was arrested in September of 1920, when I came out of the courtroom.

There weren’t any words passed between anybody except me and a deputy sheriff. When I came out of the building this deputy asked me where I was going, and I told him to the Southside. He asked me for a ride and we got in the car together and left. There was a big crowd hanging around in front of the building, but nobody else said anything to me. It just didn’t happen, that’s all. Charley Owens just made up a good story and wrote it. Oh, I would have saiad it ain’t so, all right, just like I’m saying now.

They write a lot about what a great team the White Sox had that year. It was a good team. I won’t take that away from them. But it wasn’t the same kind of team Mr. Connie Mack had at Philadelphia from 1910 to 1914. I think that was the greatest team of all time. Our team didn’t have but two hitters high in the .300’s, Mr. Eddie Collins, as fine a man as there ever was in baseball, and me. It wasn’t a hard-hitting team, not the kind they make out it was.

It was sort of a strange ball club, split up into two gangs. Collins and Chick Gandil were the two leaders. They played side by side at second and first, but they hadn’t spoken to each other off the field in two seasons. Bill Gleason was the manager, but Collins ran the team out on the field. Cicotte was the best pitcher in the league, next to Walter Johnson, I guess. They called Williams the biggest and the littlest man in baseball. He had a great big neck and shoulders, but a small body. He had only been up two or three years when he was kicked out. Looked like he would have been a real fine pitcher.

They hadn’t thought much about Dickie Kerr in the World Series, at least not for the sort of pitching he did. Red Faber was the relief man mostly. We had Swede Risberg at short and Buck Weaver at third, me and Hap Felsch and Nemo Leibold in the outfield, and one of the smartest catchers ever, Ray Schalk. It was a good ball club, but not like Mr. Mack’s.

I’ll tell you the story behind the whole thing. The trouble was in the front office. Ban Johnson, the president of the American League, had sworn he’d get even with Mr. Comiskey a few years before, and that was how he did it. It was all over some fish Mr. Comiskey had sent Mr. Johnson from his Wisconsin hunting lodge back about 1917.

Mr. Comiskey had caught two big trout and they were such beauties he sent them to Mr. Johnson. He packed the fish in ice and expressed them, but by the time they got to Chicago the ice had melted and the fish had spoiled. They smelled awful and Mr. Johnson always thought Mr. Comiskey had deliberately pulled a joke on him. He never would believe it any other way.

That fish incident was the cause of it all. When Mr. Johnson got a chance to get even with Mr. Comiskey, he did it. He was the man who ruled us ineligible. He was the man who caused the thing to go into the courts. He did everything he could against Mr. Comiskey.

I’ll show you how much he had it in for him. I sued Mr. Comiskey for the salary I had coming to me under the five-year contract I had with the White Sox. When I won the verdict – I got only a little out of it – the first one I heard from was Mr. Johnson. He wired me congratulations on beating Mr. Comiskey and his son, Louis.

I have heard the story that Mr. Comiskey went to Mr. Johnson on his deathbed, held out his hand and asked that they let bygones be bygones. They say Mr. Johnson turned his head away and refused to speak to him.

I doubt if I’d have gone back into baseball, anyway, even if Judge Landis had reinstated me after the trial. I had a good valet business down in Savannah, Georgia, with 22 people working for me, and I had to look after it. I was away from it about a year waiting for the trial. They served papers on me which ordered me not to leave Illinois. I finally opened up a little place of business at 55th and Woodlawn, across from the University of Chicago. It was a sort of pool room and sports center and I got a lot of business from the University students.

I made my home in Chicago, but I didn’t follow orders completely. I sneaked out of Illinois now and then to play with semi-pro teams in Indiana and Wisconsin. I always asked my lawyer, Mr. Benedictine Short, first, and he told me to go if I could get that kind of money.

They kept delaying the trial until I personally went to the State Supreme Court judge, after which he ordered me that the case be heard. They tried me and Buck Weaver together, and it took seven weeks. They used three weeks trying to get a jury, and I was on the witness stand one day and a half. After it was all over, Katie, my wife, and I went on back to Savannah, settled down there, and lived there until we came back to Greenville to bury my mother in 1935.

I have read now and then that I am one of the most tragic figures in baseball. Well, maybe that’s the way some people look at it, but I don’t quite see it that way myself. I guess one of the reasons I never fought my suspension any harder than I did was that I thought I had spent a pretty full life in the big leagues. I was 32 years old at the time, and I had been in the majors 13 years; I had a lifetime batting average of .356; I held the all-time throwing record for distance; and I had made pretty good salaries for those days. There wasn’t much left for me in the big leagues.

All the big sportswriters seemed to enjoy writing about me as an ignorant cotton-mill boy with nothing but lint where my brain ought to be. That was all right with me. I was able to fool a lot of pitchers and managers and club owners I wouldn’t have been able to fool if they’d thought I was smarter.

I guess right here is a good place for me to get the record straight on how I got to be “Shoeless Joe.” I’ve read and heard every kind of yarn imaginable about how I got the name, but this is how it really happened:

When I was with Greenville back in 1908, we only had 12 men on the roster. I was first off a pitcher, but when I wasn’t pitching I played the outfield. I played in a new pair of shoes one day and they wore big blisters on my feet. The next day we came up short of players, a couple of men hurt and one missing. Tommy Stouch – he was a sportswriter in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the last I heard of him – was the manager, and he told me I’d just have to play, blisters or not.

I tried it with my old shoes on and just couldn’t make it. He told me I’d have to play anyway, so I threw away the shoes and went to the outfield in my stockinged feet. I hadn’t put out much until along about the seventh inning I hit a long triple and I turned it on. That was in Anderson, and the bleachers were close to the baselines there. As I pulled into third, some big guy stood up and hollered:

“You shoeless sonofagun, you!”

They picked it up and started calling me Shoeless Joe all around the league, and it stuck. I never played the outfield barefoot, and that was the only day I ever played in my stockinged feet, but it stuck with me.

When I started out in the majors a fellow named Hyder Barr and me reported to the Athletics in the middle of the season. We got in right close to game time one day, so we checked our bags at the station and went straight to the park. They were playing the Yankees, and I hit the first pitch Jack Warhop threw me for a double. I got a single later and had two for three.

But I didn’t stick around Philadelphia long then. I went back to the station to get my bag that night, and while I was waiting for it I heard the station announcer call out: “Baltimore, Washington, Richmond, Danville, Greensboro, Charlotte, Spartanburg, Greenville, Anderson” and so on. I couldn’t stand it. I went up to the window and bought a ticket to Greenville and caught that train.

Sam Kennedy came after me on the next train. He found out I’d gone from Barr. I was supposed to get Barr’s bag, too. He was quite a ladies’ man and he’d taken up with some girl while I went for the bags. When I didn’t come back, he came after me and found out I’d gone.

That was just the first time. I went back with Sam Kennedy, after he offered me more money. But I came home three other times before that season was over. It wasn’t anything I had against Mr. Mack or the ball club. Mr. Mack was a mighty fine man, and he taught me more baseball than any other manager I had. I just didn’t like Philadelphia.

I was traded to Cleveland later on and I liked it there. Charley Somers, who owned the Indians, was the most generous club owner I have ever seen. We couldn’t play Sunday ball in Washington then, and when we were playing the Senators over a weekend, we’d make a jump back to Cleveland for a Sunday game, then back to Washington Sunday night. There never was a time we made that jump that Charley Somers didn’t come down the aisle of the train and give all the players $20 gold pieces.

He was a generous man when it came to contracts, too. The first year I came up to Cleveland, in 1910, I led the league unofficially in hitting. When I went to talk contract with him for 1911, I told him I wanted $10,000. He wasn’t figuring on giving me more than $6,000, and he wouldn’t listen to me.

“I’ll make a deal with you,” I told him. “If I hit .400 you give me $10,000. If I don’t, you don’t give me a cent.”

It was a deal, and I signed the contract, and I hit .408. But I still didn’t win the American League batting title. That was the year Ty Cobb hit .420. I was hitting .420 about three weeks before the season was over and Mr. Somers called me in to pay off, told me I could sit it out the rest of the season. I told him to wait until the season was ended and I wasn’t quitting. I wrote my own contract the rest of the time I was at Cleveland.

Babe Ruth used to say that he copied my batting stance, and I felt right complimented. I was a left-handed hitter, and I did have an unusual stance. I used to draw a line three inches out from the plate, from the front to the back of the plate every time I went to bat. I drew a right-angle line at the end next to the catcher and put my left foot on it exactly three inches from the plate. I kept both feet together, then took a long stride into the ball.

The say I was the greatest natural hitter of all time. Well, that’s saying a lot with hitters like Wagner, Cobb, Speaker, and Ruth around. I had good eyes and I guess that was the reason I hit as well as I did. I still don’t use glasses today.

I have been pretty lucky since I left the big leagues. No man who has done the things they accuse me of doing could have been as successful. Everything I touched seemed to turn to money, and I’ve made my share down through the years. I’ve been blessed with a good banker, too – my wife. Handing money to her was just like putting it in the bank. We were married in 1908 when I was just 19 and she was 15, and she has stood by me through everything. We never had any children of our own, but we raised one of my brother’s boys from babyhood.

He never was interested in baseball, but they used to tell me he would have been a fine football player. He didn’t get to go to college. The war came along and he went into the Navy as a flier. He was killed accidentally a couple of years ago when a gun he was cleaning went off. Katie and me felt like we’d lost our own boy.

I hadn’t been able to do much work for a year until last Summer because of liver trouble. A good doctor in Greenville took my case when I thought my time was about here, and he brought me back to good health. I went back to my liquor store last July and I’m running the business now myself. I had leased it out while I was sick. I’ve been doing about $50,000 to $100,000 a year business.

Some people might think it’s odd, but I still have a connection in baseball, sort of a judicial connection, I guess you’d call it. I am chairman of the protest board of the Western Carolina Semi-Pro League. I think that is an indication of how I stand with my own people. They have stood by me all these years, the folks from my mill country, and I love them for their loyalty.

None of the other banned White Sox have had it quite as good as I have, I understand, unless it is Williams. He is a big Christian Science Church worker out on the West Coast. Last I heard, Cicotte was working in the automobile industry in Detroit. Felsch was a bartender in Milwaukee. Risberg was working in the fruit business out in California. Buck Weaver was still in Chicago, tinkering with softball, I think. Gandil is down in Louisiana and Fred McMullin is out on the West Coast. I don’t know what they’re doing.

I’m 61 years old now, living quietly and happily out on my little street close to Brandon Mill. I weighed 186 and stood six feet, one inch tall in my playing days. I’m still about the same size.

There never were any other ballplayers in my family that went to the big leagues. I had five brothers, but only one, Jerry, played pro ball long. He was a pretty good minor-league pitcher, they tell me. Jerry’s 48 years old now and he’s one of my umpires in the Western Carolina League.

Well, that’s my story. I repeat what I said when I started out – that I have no axe to grind, that I’m not asking anybody for anything. It’s all water over the dam as far as I’m concerned. I can say that my conscience is clear and that I’ll stand on my record in that World Series. I’m not what you call a good Christian, but I believe in the Good Book, particularly where it says “what you sow, so shall you reap.” I have asked the Lord for guidance before, and I am sure He gave it to me. I’m willing to let the Lord be my judge.

In this photo, Joe Jackson (right) is talking with Furman Bisher, who was a well-known and respected columnist for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution for 59 years. This photo was taken in the Jackson's front yard in 1949, and the interview was one of only a very few that Joe ever gave about the 1919 World Series scandal. Permission to reprint the article was granted by Tom Ficara, Publisher, SPORT Magazine.