Joe’s Story

The great Ted Williams once remarked: “When I was younger, the Red Sox used to stop sometimes in Greenville, South Carolina – that’s Joe Jackson’s home. And he was still alive. Oh, how I wish I had known that and could have stopped in to talk hitting with that man.”

Many of us wish we could have talked with Joe Jackson!

There are still folks around the Greenville area who knew Joe. Most of them were kids during the ‘40s when they learned to bat and throw from the old man who ran the liquor store on Pendleton Street. Years later, only after Joe was gone and they were grown, did they understand that “Mr. Joe” had been one of America’s greatest ballplayers.

Joe Jackson came from a hard life of southern poverty. He was born on July 16, 1887 in Pickens County, the first of six boys and two girls born to George and Martha Jackson. When Joe was six years old, he went to work at Pelzer Mill, sweeping cotton dust off the wooden floors.

In early 1901, George Jackson moved his family to the Brandon community of West Greenville, South Carolina. Life was tough for the large family, and like so many children of textile mill workers, Joe went to work to help his family. There was no time for school, so Joe never learned to read or write. He probably would have spent the rest of his life working in the textile mills if it weren’t for baseball.

At an early age, Joe showed signs of greatness at bat and in the field. By the time he was 13 years old, he was playing on the Brandon Mill men's baseball team. Folks said they could be blindfolded and still know when Joe hit the ball because they heard that special 'crack!' When he’d hit a home run or make a great defensive play in the field, his brothers would scatter through the crowd, passing their hats for tips. They would sometimes make as much as $25.00 in a single game.

Joe's home runs were known as "Saturday Specials." His line drives were "Blue Darters." His glove was "The place where triples go to die." And he could throw the ball around 400 feet on the fly. Crowds cheered at just the sight of Joe coming to the on-deck circle. Many years later, the great Ty Cobb told Joe: "Whenever I got the idea I was a good hitter, I'd stop and take a look at you. Then I knew I could stand some improvement."

In 1908, Joe was playing semi-pro ball with the independent Greenville Spinners. During the game on June 6 against the Anderson Electricians, Jackson’s brand new cleats quickly wore painful blisters on his feet. Halfway through the game, Joe took off his spikes to… ease his pain. In the bottom of the 7th, Joe hit the longest home run in the history of Memminger Street Park, the home field of the Spinners. In just his socks. As he rounded third base on his home run trot, a fan of the opposing team shouted, "You shoeless son-of-a-gun!" It was the only time Joe played 'shoeless' in a game, but he was tagged with the moniker "Shoeless Joe," and the name stuck.

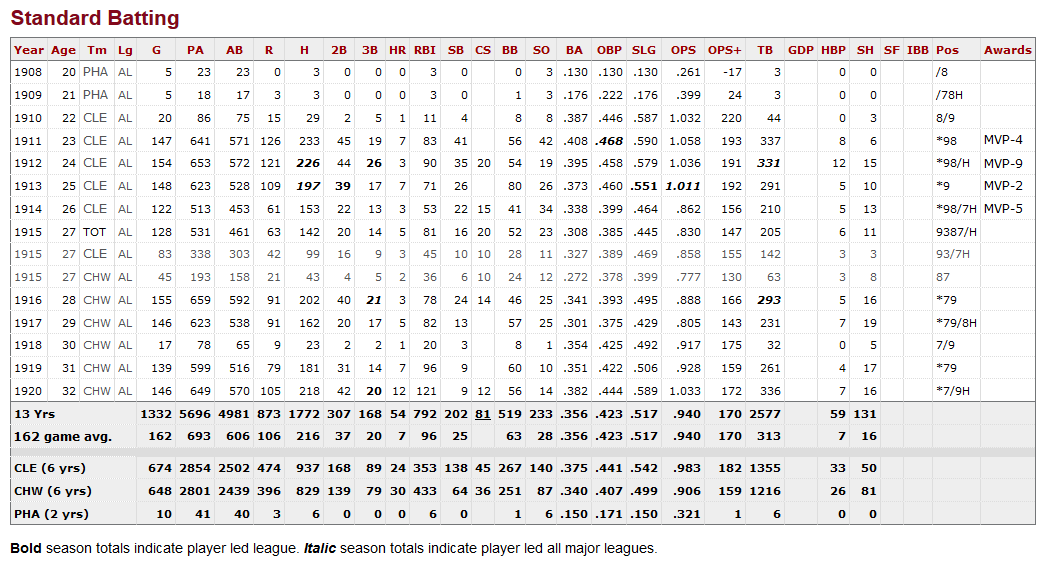

It didn’t take long for word of Jackson’s quick instincts and precise skills on the baseball field to reach the professional leagues. Connie Mack signed him with the Philadelphia Athletics in August of 1908. In 1910, Mack traded him to Cleveland. The following year, in his first full season in the majors, Joe batted .408, the highest batting average ever recorded by a rookie.

In August of 1915, Joe was traded again, this time to the Chicago White Sox for $31,500 cash and three players. The White Sox were a talented team, winning the World Series in 1917 and the American League pennant in 1919. They were the heavy favorites to beat Cincinnati in the 1919 World Series, but the Reds ultimately won the series.

In response to suspicions that the White Sox were under the influence of sports bookies, Joe Jackson and seven other White Sox players, were accused of conspiring to throw the 1919 World Series.

The headline, “WHITE SOX INDICTED!” stunned baseball fans. At the trial in 1921, however, it took only two hours for a Chicago jury to render a verdict of not guilty on all counts. Despite acquittal in a court of law, and without conducting an investigation, baseball’s newly appointed baseball commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, banned Jackson and seven other White Sox from playing professional baseball, sending a no-tolerance message regarding gambling in baseball.

Whether Joe Jackson really helped fix the 1919 World Series has remained a point of dispute for over a century. Joe played nearly flawless baseball. He hit .375 for the series, the highest on either team. He had twelve hits (a World Series record which stood for nearly 50 years before it was broken). He collected six RBIs and accounted for 11 of the 20 White Sox runs. He didn’t commit a single error in the field in the eight games, and he threw out five Reds baserunners from the outfield. Oh, and he hit the only home run in the series. For either team.

Joe told The Sporting News in 1942:

"Regardless of what anybody says, I was innocent of any wrong-doing. I gave baseball all I had. The Supreme Being is the only one to whom I’ve got to answer. If I had been out there booting balls and looking foolish at bat against the Reds, there might have been some grounds for suspicion. I think my record in the 1919 World Series will stand up against that of any other man in that series or any other World Series in all history."

Following his banishment from professional baseball, Joe and his wife, Katie, moved to Savannah, Georgia in 1922. While there, the couple owned a dry-cleaning business which was so successful they had to open a second location. When Joe’s mom got sick in 1932, the Jacksons moved back to Greenville to take care of her. They opened a barbeque restaurant on Augusta Street until Prohibition ended. Later, they opened a liquor store on Pendleton Street, just a stone's throw from Brandon Mill where they both grew up. During baseball season, Joe played with semi-pro teams throughout the south, and sometimes even with teams in the north. In 1941, at the age of 53, Joe put on a hitting exhibition and belted two home runs in the process.

But Joe's story doesn't end here. Evidence of what actually occurred before, during and after the 1919 World Series - who was involved, and who covered up the truth - is beginning to surface. Fortunately, the Black Sox Scandal is being studied by respected baseball historians who are exposing a cover-up that has long been suspected, but never proven.

Joe Jackson continues to be one of the most beloved and publicized ballplayers of all time. Several movies, a Broadway play, songs, poems, countless books, television documentaries, feature articles and now the internet and social media have spun Joe Jackson into an American icon. And the legend continues to grow…

Joe’s Stats

Stats courtesy of Baseball Reference. For Joe’s full defensive statistics, postseason statistics, minor league statistics, and more, click the image to be taken to his full Baseball Reference player profile.