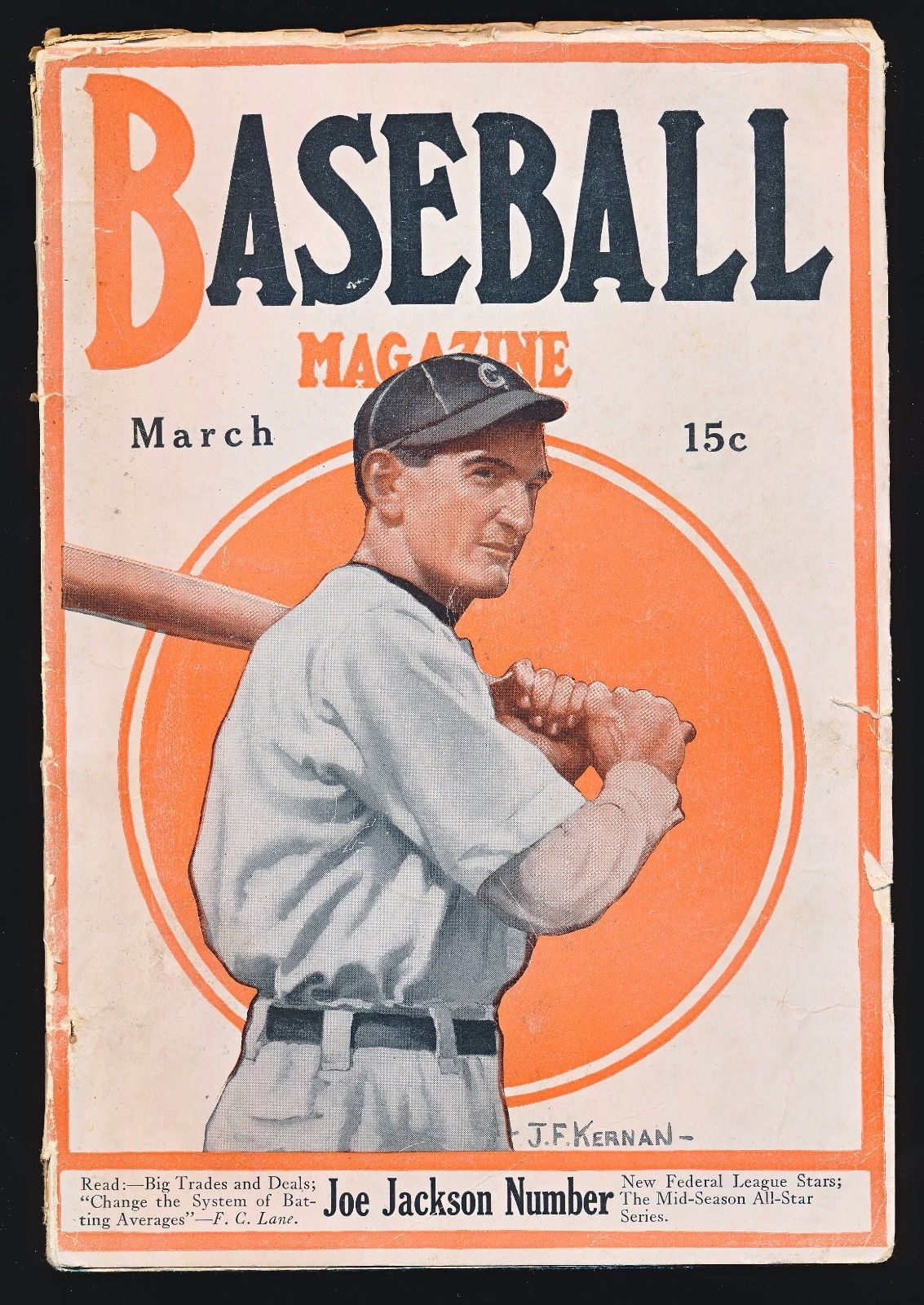

Baseball Magazine - March, 1916

This issue of the magazine is commonly referred to as the “Joe Jackson Number” and is the most sought-after copy of the magazine’s entire run, which lasted from 1908 to 1957.

The cover artwork was done by the prolific Joseph Francis Kernan, whose illustrations graced the covers of The Saturday Evening Post, The Country Gentleman, Outdoor Life, Collier’s Liberty, Capper’s Farmer, The Elks, and the Associated Sunday Magazines, in addition to many Baseball Magazine issues.

The Man Who Might Have Been The Greatest Player in the Game

Joe Jackson and His Extraordinary Career – A Humble Beginning – His Sensational Rise – His Strong Points and Weaknesses as a Popular Star

BY F. C. LANE

Joe Jackson will be known in after years as the man who might have been the greatest player the game has ever known. To sum up his talents is merely to describe in another way those qualities which should round out and complete the ideal player. In Jackson, nature combined the greatest gifts any one ball player has ever possessed but she denied him the heritage of early advantages and that well balanced judgement so essential to the full development of his extraordinary powers. Joe Jackson is the most striking example in history of what a player can accomplish on sheer ability.

The oddest character in baseball today is that brilliant but eccentric genius, Joe Jackson. Those who know him best are readiest to admit they know him least. So strange a medley of contradictory traits, of weaknesses and errors, sustained throughout by sheer natural ability no atom short of marvelous has never been seen elsewhere in that region of queer personalities and clay footed popular idols known as major league baseball. Jackson is unique unparalleled; dramatic in his rise to prominence, brilliant in his success, startling in his manifold failures. His is a character that has never been exploited, that probably never will be exploited until he has passed forever from the diamond and given the perplexed scribes a proper perspective of his mingled weaknesses and dazzling talents.

But the public is impatient. It doesn’t want to wait until a man is dead or gone from active life before it checks up its estimate of his worth. So we will endeavor, from an intimate knowledge of Joe Jackson’s early surroundings and a close association with him personally ever since he broke into the major leagues, to trace the broken corners of that character which has so impressed its distorted image on the public fancy.

We have interviewed numberless people about Joe Jackson, from Charles Somers and Charles Comiskey down. We have been in his native town and seen the mill where Jackson worked as a humble employee through the years of his youth and listened to the opinions of his boyhood friends. We have heard his mother tell about “Her Joe” and talked with four of his five brothers. We have discussed his case with his first manager and with most of his subsequent managers. And lastly, we have spent as much time with Joe personally as with any other player in the game. And the numberless stories and traditions of Joe and his many eccentricities, when traced to their source, reveal an absolute maze of contradictions most difficult to resolve to truth.

Joe himself has a warm, fervid imagination, which looks upon facts as hurdles to be surmounted by brief but frequent flights of fancy. If he had that education which is the proper endowment of an American he might become a great writer, for we would back his imagination against the world. But other sources of information are not thus hampered by an exotic growth of fiction and yet they throw rays of light the most diverse upon the character of the high strung Southerner.

Perhaps the best estimate of a man may be had by steering a median course between extreme opinions. When Birmingham was manager at Cleveland, while the sun still shown brightly upon Charles Somers’s fortunes, he told me that he would not trade Joe Jackson for Ty Cobb. “I consider Joe the greater asset to a club of the two,” said he.

Another warm admirer of Joe Jackson is Walter Johnson, the uncrowned king of American League pitchers. “I consider Jackson the greatest natural player I ever saw,” was Walter’s comment.

Pitted against these complimentary views are two others taken at random from an indefinite list. I recall overhearing a conversation between two fans at the Polo Grounds. Joe Jackson was standing near with his back toward the grandstand. He has a build almost exactly like that of Ty Cobb. One of the fans, noting this similarity, said: “Joe looks a good deal like Ty Cobb, doesn’t he?” “Yes,” retorted the other fan, “he is a good deal like Ty Cobb — from the neck down.”

I was talking with an early acquaintance of Jackson’s at Greenville. Possibly the comments of this early acquaintance were tainted by jealousy or other unworthy motives, but at any rate he summed up the success of his fellow townsman in this manner: “Joe’s record is the best example I ever saw of what a man may accomplish in this world wholly without brains.”

This opinion we are bound to confess is extreme. Joe has brains, in fact he is remarkably keen-witted about many things. But we doubt if his brains ever helped him greatly in his baseball career. For his success is due solely to an extraordinary natural ability that has certainly never been surpassed and has probably never been equaled.

The last phrase of the above sentence will be deeply criticized. But let us see. Ty Cobb has dominated the past decade in baseball history and established the brightest record in baseball annals. Ty Cobb is universally admitted to be the greatest player of the present and except for the croaking of a few old-timers is equally admitted to be the greatest player of all time. Ty has a marvelous baseball brain, a brain that works even faster than his body, a brain that is worth a fortune to any man. But Cobb would never have established the records he has established if he had not possessed as an accompaniment of that brain a wealth of natural ability of the very first order. But let us see how he compares with Joe Jackson.

Ty is a wonderful batter. Most of his reputation rests upon his phenomenal work with the stick. And yet we will maintain that Joe Jackson is a better natural hitter than Ty Cobb by a considerable margin. Ty’s record in the minors was brief and meteoric. His entry into the majors was sensational, but he did not immediately show that speed and dash which has characterized all his efforts since that time. In short, as Ty matured he grew better, and this was so merely because Ty was gearing his brain to his speed and batting eye and making of himself that wonderful mental and physical machine which he is to-day. But Jackson, when he became a professional ball player, established a record which so far as we know has never been equalled. First with the Carolina Association, then with the South Atlantic League, next with the Southern League, and lastly with the American League, Joe Jackson led each league in batting in his very first season.

Knowing little of the inner science of baseball, untutored, feeling friendless and alone in the great world far off from his little home circle, depending upon no one but himself, he leaped from height to height, growing better as he advanced, always showing a little better than the next best man could show. In the American League he found the greatest batting race of all history waged to its furious conclusion between Lajoie and Ty Cobb. Cobb’s average stood at .385, but Jackson topped it with .387. He took part in too few games to count as the batting leader, but he led the league, nevertheless. The next season Jackson, the natural prodigy, accomplished the impossible. He crossed the .400 mark, which had been deemed closed for all time to the batsman by the introduction of the foul strike rule. He hitfor .408 and forced the desperate Ty to the utmost limit of his strength and cunning to keep ahead of him.

This marvelous record Joe accomplished on sheer ability. Ty Cobb was wise in the arts of baseball, crafty, farsighted, lightning-brained. Joe Jackson had simply native gifts, which, in themselves, have never been equaled. It was as natural for him to hit a baseball as it was for his early forebears to hit a squirrel in the eye at a hundred yards. When Joe batted for .408 he did far better than did Ty Cobb with .420 to his credit, for Cobb, as every one knows, beats out many a lean hit by dazzling speed and quick wit and constantly harasses the pitcher and the infielders by the wealth of tricks of which he is master. But Joe stood silent and alone at the plate and banged out the best the pitchers could offer him to the tune of .408. Surely his like as a natural batter has never been known.

As a fielder Joe is like the image of Daniel’s vision, partly iron and partly clay. He has made stops that were seemingly impossible. I saw him once make that rarest of plays, a putout at first on a bouncing fly. He is a keen judge of distance, he has great natural speed, and his throwing arm is so extraordinary as to elicit from Walter Johnson the comment that it was the best he ever saw. Naturally, Joe might be the greatest outfielder in the world. In actual fact his performances in the field, like most of his performances, leave much to be desired.

Ty Cobb is a great outfielder, but his superiority to Jackson rests wholly upon brain and mental keenness. Joe certainly has as great natural gifts as Ty and his throwing arm is considerably better.

As a base runner Ty is a marvel. But if we analyze his record we will see that his superiority rests entirely upon the mental basis. Jackson has an even better build for running. Just as tall, he is lither, more sinuous and lighter. Furthermore, even Ty will admit that in a straightaway race Jackson is just as fast as he. And his hook slide, the most important of the items in base running, is as near perfection as may be.

Joe Jackson combined in one frame natural ability to make him the greatest ball player the game has ever known. It is singularly unfortunate that these amazing talents are not combined with a better mental training and sounder judgment.

Joe Jackson’s records, those which appear outwardly, at least, are fairly well known. But to understand a man as he is we must follow him back into the obscurity of childhood and the seclusion of private life. The oldest of six brothers and two sisters, Joe was born on a plantation with an unpronounceable name, some twelve miles from Greenville, South Carolina. Here, in the literal backwoods, he spent the first few years of his life. The plantation belonged to an eccentric old fire-eater, whose dealings with his tenants were not always of an amicable nature. The Jacksons derived a meager living from the soil, for the plantation supported acres of cotton, some corn, and the customary lean cattle and razorback hogs of the poorer sections of the South. It was the land of corn whiskey and the black pall of illiteracy rested like a blight upon the inhabitants.

The incidents of such a childhood can be understood and appreciated only by one who has passed through them. Now, Greenville is a clean-kept city of some fifteen thousand people, which felt the quickening touch of northern enterprise. Around its environs, one after the other, long spacious structures were erected and dedicated to the manufacture of cotton, the heritage of the South. Eleven great factories dot the landscape in the environs of Greenville and in the suburbs are miniature mill villages with a combined population of some twenty thousand persons. It was to one of these mill villages which grew up around the great Brandon cotton manufactory that the elder Jackson journeyed, carrying with him his numerous family. The wage in the cotton mills, while small, was secure and looked welcome to a member of the poor white population of the country districts.

In the hot and stuffy rooms of the Brandon mill Joe Jackson toiled for six years, beginning when he was thirteen years old. The hours were from six to six, the work unwholesome, and in some cases dangerous. The surroundings, outside the mill, were of the factory town variety. Between the population of Greenville proper and the mill villages on the outskirts there was a great gulf fixed.

The Brandon mill, like many other business enterprises, promoted a baseball club for its employees. Upon its payroll of eight hundred names that of Joe Jackson was written big almost from the first. His mother told me that the men in the mill would come for Joe when he was but thirteen and want him to play on their teams. Though nothing but a boy, he possessed from the start that keen batting eye which has been his chiefest bid to fame. Joe did not start as an outfielder, either. He was a catcher.

“Joe has a scar on his forehead,” said his mother, “that he got in those early days. He was catching behind the plate and a great burly mill-hand was pitching to him. He threw one so swift and strong that Joe didn’t have strength enough to stop it. So it forced his hands back, drove into his mask and dented the mask into his forehead, leaving a deep cut. That was how he got that scar.”

The secretary of the Brandon Mills, Mr. J. C. Hatch, informed me that he was manager of the local mill team when Joe was a member. “He was a great natural batter even then,” said Mr. Hatch. “Of course he wasn’t a finished ball player by any means, and those of us who knew him never imagined that he would make much of a reputation outside the mill. But he developed rapidly, once he had the opportunity, and the whole country knows his record now.

“I well remember the first game Joe ever tried to pitch. So far as I know, it was the last game as well. He had a remarkably strong throwing arm, and some of us imagined that, with that whip of his, he ought to be a great pitcher. Perhaps he would have been, but one game cured him. He was pitching to one of the mill-hands here, and, like all amateur pitchers, burning over the ball with all the speed at his command. Unfortunately the ball hit this particular mill-hand on the arm and broke his arm. Joe decided that if he were that dangerous in the box he had better play some other position.

“Joe’s father worked in the mill most of these years, but finally got into some disagreement with the management and decided to go into business for himself as a butcher, supplying meat for the mill operatives. The business was a small one, but Joe occasionally helped him in the business when work at the mill was slack.

“I remember the elder Jackson as a man with abnormally long arms. I never heard that he was particularly athletic — simply one of the wiry type of South Carolina backwoodsmen. He died about two years ago. Joe seems to have been athletically inclined from the first. He certainly has an ideal build.”

Baseball instinct seldom runs in families, but Joe’s younger brother Dave showed much promise as a ball player. His family and friends apparently expected great things from Dave, and indeed he did become a professional ball player in a small way, but Dave met with so many accidents in the mill that he was practically debarred from any hopes of success on the diamond. He broke his right arm while employed in the mill on no fewer than five occasions, having become caught in the whirring machinery.

Once he was carried to the roof by a revolving belt, and not only his arm but one leg broken. The many fractures of his arm have bent it slightly and stiffened it so that he has some difficulty in catching a ball under certain circumstances. It would seem that a young man who has suffered so many mishaps would be incapacitated for almost any athletic work.

When Joe left the mill he had perhaps gone as high as he could ever expect to go, with a wage of $1.25 a day. His entry into the ranks of the professional ball player came in this wise.

In 1907 he was playing with a mill team at Greer, South Carolina. Against this team came a neighboring aggregation under the leadership of Thomas Stouch, later manager of the Greenville club. Stouch is the man who is really responsible for Jackson’s rise to fame — the man who gave him his first professional engagement, and who tipped off Connie Mack to the ability of his mill-hand star, and really introduced him into major league ranks.

But we will let Mr. Stouch tell the story of his first meeting with Jackson:

“I had been appointed manager of the Greenville club,” he says. “Naturally, while scouring around the country, I was on the outlook for new talent. I was playing second base on this particular occasion, when a tall, thin fellow stepped to the plate. He didn’t appear to have it in him, but he drove the ball on a line toward the very spot where I was standing; like a bullet out of a gun. Now I have had much baseball experience and though getting a little old for active service, I still prided myself that I knew how a ball ought to be fielded. But that pellet caromed off my shins before I had time to make any effort to field it, and it hurt my shins, too, depend upon that. I thought to myself, ‘If this Rube hits them like that every time, he must be some whale. I guess he will bear watching.’ He did. That game, if I remember, he made three hits, two of them for extra bases, and they were all ringing smashes that left a trail of blue flame behind them when they shot through the air.

“I got into consultation with my pitcher and said to him, ‘Bill, you watch this young fellow and see if you can discover his weakness.’ We played five games in all at the burg, and every day Jackson walloped the ball as he had done at the first. The last day he drove one straight at Bill’s head. Bill looked at it for about a thousandth of a second, and then ducked as if he were dodging a shell from a Krupp mortar.

“ ‘Did you discover his weakness?’ I asked Bill after the game was over. ‘No,’ replied Bill, ‘but he discovered mine, all right. I don’t want to buck my head against any of those wallops.’

“After the series I went and hunted up Jackson. ‘I am going to manage Greenville next year,’ I told him, ‘and I would like to have you play with me, if we can agree upon terms. ‘All right,’ said Joe; ‘I would like to play with Greenville.’ ‘How much are you getting now?’ I asked; ‘$35 a month in the mill,’ replied Joe. ‘Very well,’ said I, ‘how much do you want to play for me?’

“ ‘Well,’ said Joe, ‘you see, I am getting along pretty well. I get $35 a month from the mill, but I get $2.50 a game on Saturdays for playing ball, so that gives me $45 a month in all. I wouldn’t want to give up my job unless I could see something in sight. I think I ought to be worth $65 a month to you.’

“‘Joe,’ I said, ‘if you will promise to let corn whiskey alone and stick to your business, I will pay you $75 a month.’

“ ‘I will work my head off for $75,’ said Joe, and that was our bargain. “What Joe did at Greenville next year — which was the season of 1908 — is history now. He led the league, as, in fact, he has led every league he ever played with. And he developed so fast that I was determined to sell him into major league company.

“I am an intimate friend of Connie Mack and drifted down here, I hardly know how, when I grew too old to play baseball in fast company. So naturally my first thought was of Mack and the Athletics. I notified Mack of my find, and Mack promptly wired to bring him on.

“Jackson is, in many respects, a queer fish, as you know, and when I told him I was going to take him to the big leagues, he didn’t show the enthusiasm I expected he would. ‘I hardly know how I would like it in those big northern cities,’ he told me. ‘Oh, you will like it fine there,’ I said; and so I started north with Jackson. I don’t remember the exact town, but it was somewhere en route that Joe slipped off the train, unknown to me, and got the next train back home. I thought he had gone into another car — never even dreamed that he wasn’t on the train — until I got to Philadelphia. It was a mortifying position to be in, and I was anxious for fear something had happened to Joe, when we got a telegram. He had got someone to send it for him, and it read something like this, ‘Am unable to come to Philadelphia at this time.’

“ ‘What does this mean?’ said Connie. And then I tried to explain the situation. “When he understood it, Mack said to ‘Socks’ Seybold, ‘Go down to Greenville, and get this fellow’s brothers and sisters, and his whole family, to come back with you, if necessary, but bring him with you, and see that he doesn’t give you the slip on the way.’ So Joe came back a second time to Philadelphia.

“He took part, as I remember it, in one game, and did fairly well, though he muffed a fly. But the next two days it rained. Detroit was the next club in town, and around the lobby the fellows got to talking about Ty Cobb and comparing him with Joe. Joe listened to all that was said, and I never knew why he should be affected as he was. Perhaps it was for fear that he would not look very strong against the greatest player in the game. Perhaps it was for some other reason, but the next morning Joe caught the 6:15 train for Greenville.”

Joe’s connections with the Athletics continued from 1908 to 1910, and have been the theme of much comment. During these years he put in little enough time with the Athletics, but was farmed to other clubs and made a prodigious reputation with several minor leagues. He was with Savannah in 1909 and led the South Atlantic League with a batting average of .358. He was with New Orleans in 1910, and led the Southern League with .354.

“Charles Somers was owner of the New Orleans club. After several discouraging interviews with the eccentric Jackson, Mack rather soured on his purchase, as he is apt to do upon occasion. Somers had Briscoe Lord and offered cash to boot, so Mack said good-bye to his talented but unmanageable find. With Cleveland in the fall of 1910 Joe struck the record clip of .387, and bettered it the following year with .408 to his credit. He burned up the circuits like a whirlwind once he got fairly started.”

Joe’s backing and filling with the Athletics form an intricate chapter, and one that is extremely hard to understand. But to one who has known him and the little circle which was his whole horizon at the time, his conduct is more clearly grasped. Joe is confident — in a way perhaps overconfident — but he has lacked at all times that innate faith in himself which is the groundwork of success. Prosperity came too quickly to Joe, and he couldn’t grasp it all at once. The rise from the dust and smoke of the cotton mill to fame on the local diamond at Greenville was dazzling enough for his mental horizon. When it came to a regular position on a great metropolitan team in that strange world of the North, which was as a foreign land to him, it was a different proposition. Joe felt entirely out of place. He was homesick for the pines and cotton fields of his native South. He was entirely unused to city ways, and the routine of a big metropolitan hotel. It was a strange new world to Joe, and he felt the instinct to run away from it all, back to the world that he knew.

With success in other and larger cities culminating in New Orleans, Joe was ripened for entry into major league life at Cleveland. He had become used to customs which tallied not at all with his days of poverty when he was Shoeless Joe, the ignorant country lad, the poor mill-hand who played baseball for pastime or for $2.50 a game. He had become used to city ways, he had demonstrated what he could do, he had discovered that he had it in him to rival the greatest at his chosen profession, he had become acclimated, as it were, to a world that had been wholly foreign to his tastes and experiences.

His mother, anxious to shield her son from any vestige of blame, explained the seeming eccentricities of his conduct with the Athletics in the following way: “Joe has been accused of running away from Philadelphia,” she said, “and that would imply that Joe hasn’t courage. It is a great mistake. Joe is game, and he has always been game. He left Philadelphia because I sent for him. His wife was very sick and his uncle was not expected to live. Any man whose relatives were in that condition could not refuse to come to them when they sent for him. And I don’t see how anyone can criticize Joe for doing what any man with any self-respect could not help doing.”

Joe’s record has been a brilliant but tarnished one. He started out like the world-beater that he is. He took the whole minor league system by storm and vaulted at one leap to the very pinnacle of the American League. He contested for three years with Ty Cobb for the batting crown, and was beaten out only by the superior adroitness and address of his brilliant rival. For three years he made the fiery Georgian extend himself for every step of the way.

Then the dissipations which assail the ball player in the big cities of the circuits began to exert their fatal glamor on Joe. Or, rather, his strong constitution began to show the effects of these dissipations. Though still a wonderful ball player, the last two years have seen a substantial decline in Jackson’s once great record. It remains for the future to tell whether or not he will bring to Comiskey’s club that wonderful ability which is his by divine right.

Joe’s course in major league baseball has been the natural one. Unschooled and unlettered, he was cut off from many of the sources of amusement which appeal to the average man. To add to the various pitfalls with which the ball player has to contend in the course of his active duties, Joe had a fondness for the life behind the footlights. Last winter he was a member of a little troupe which toured the country, and this life did not prove beneficial to Joe in any way. His health was impaired, his finances became involved, and the season just closed was the poorest he has ever had.

Be it remembered, however, that Jackson’s poorest will rival most players’ best efforts. Part of the season he was laid up with genuine injuries received on the field of battle. Joe is physically game, and plays oftentimes when he should be on the shelf from injuries. “I have had him go into a game,” said Birmingham, “when I would have preferred to let him stay out and get into better shape. Spike cuts, however severe, never bothered Joe, and I have seen him line a ball in from the deep outfield, though I knew his elbow was encased in bandages from injuries at the time. Joe is game, there is no mistaking that, and you can’t keep him off the field when he can possibly play.”

Joe is a shrewd observer. In a way he is extremely ambitious. Now that he has become accustomed to handling money in larger amounts than he ever saw it before, he has learned the easy lesson to take all he can get. The Federal League, at the time it was openly fishing for stars, attracted Jackson into its net, and I remember distinctly on a visit to see President Gilmore at the Biltmore Hotel, finding the genial head of the Federal League seated in the lobby in earnest consultation with Joe Jackson.

Now that the whole grand war has become history, it will not hurt anyone to reveal the inside story of the Joe Jackson deal. On the very day before the incident of which I speak I had talked with President Somers, of Cleveland, and questioned him as to rumors that Jackson was about to be traded. “There is nothing in the story,” said Somers; “I need Jackson to build up my club.” But in the meantime Joe got it in his head that there were more plums in the orchard than he had yet plucked, and Somers, becoming convinced that he could not hold Jackson against the spirited bidding of the Federal League, sold him to one whom he knew could thus hold him, namely Charles Comiskey. The price the old Roman paid for Joe was $31,500 and three players, and the salary a substantial raise over Joe’s previous one. The criticism of the deal is a little story in itself, and we give elsewhere Mr. Comiskey’s version of the affair.

Jackson’s best year was 1911. He hit .408, made 233 hits, scored 126 runs and had a total of 41 stolen bases to his credit. The next year was nearly as good; he hit for .395, made 226 hits, scored 121 runs and stole 35 bases. Even last season, which was his poorest and which was largely broken up by injuries, indifferent playing and the glamor of the Federal League, he batted for .308.

Up to the present winter Joe has made his winter home at Brandon Mills. Here he bought a house, a much better house than any other in the mill village, which he gave to his father and mother. Here his mother and four of his brothers still reside.

Ambitious to succeed in other lines of business Joe opened a fine poolroom in Greenville, which should have proved a success with the enormous advertising of his name. But his partner in the enterprise apparently failed woefully as a manager, and the enterprise was a failure. A farm which Joe purchased near Greenville became also involved in financial mismanagement, and Joe, having learned the bitter lessons of experience, will need to make the most of his good salary and his prospects in the next five years.

Numberless efforts have been made by the various managers who have had Joe in hand to get him to overcome the handicaps of an early lack of advantages. Connie Mack offered to hire a tutor and companion for him, who would live with him and teach him the things he most needed to learn. Somers also tried to do the same thing, but to all these offers Joe turned a deaf ear. To Joe the vast domain of “book” knowledge is indeed a sealed mystery.

In temperament Joe is as variable as the wind. High strung and impetuous, he has that proud, imperious disposition which goes so frequently with Southern birth. He is sensitive, easily hurt, quick to take offense. But he is popular with his fellow players and with those who know him, and, unlike many ball players, it is safe to say that he is unpopular nowhere.

Seven years ago when he was just entering upon his professional baseball career, Joe married a little Southern girl from the environs of Greenville who was but fifteen years old. Their winter home has usually been in Greenville, in the house he purchased and gave to his father and mother. This winter, however, Joe has resided in Cleveland.

Numberless anecdotes of Jackson, some of them accurate, some tinged with fiction, but all throwing some light on his complex character, have gone the rounds of the circuits. There isn’t a city which hasn’t witnessed some prodigious feat which has stamped Jackson as a real wizard of the diamond.

Ambitious to succeed in other lines of business Joe opened a fine poolroom in Greenville, which should have proved a success with the enormous advertising of his name. But his partner in the enterprise apparently failed woefully as a manager, and the enterprise was a failure. A farm which Joe purchased near Greenville became also involved in financial mismanagement, and Joe, having learned the bitter lessons of experience, will need to make the most of his good salary and his prospects in the next five years.

Numberless efforts have been made by the various managers who have had Joe in hand to get him to overcome the handicaps of an early lack of advantages. Connie Mack offered to hire a tutor and companion for him, who would live with him and teach him the things he most needed to learn. Somers also tried to do the same thing, but to all these offers Joe turned a deaf ear. To Joe the vast domain of “book” knowledge is indeed a sealed mystery.

In temperament Joe is as variable as the wind. High strung and impetuous, he has that proud, imperious disposition which goes so frequently with Southern birth. He is sensitive, easily hurt, quick to take offense. But he is popular with his fellow players and with those who know him, and, unlike many ball players, it is safe to say that he is unpopular nowhere.

Seven years ago when he was just entering upon his professional baseball career, Joe married a little Southern girl from the environs of Greenville who was but fifteen years old. Their winter home has usually been in Greenville, in the house he purchased and gave to his father and mother. This winter, however, Joe has resided in Cleveland.

Numberless anecdotes of Jackson, some of them accurate, some tinged with fiction, but all throwing some light on his complex character, have gone the rounds of the circuits. There isn’t a city which hasn’t witnessed some prodigious feat which has stamped Jackson as a real wizard of the diamond.

His faults, which are as obvious as his virtues, are what one would naturally expect. Jackson has traveled far on the road from the bottom of the ladder. The fact that he has not accomplished everything to be desired should certainly not be held against him. The entire lack of advantages in his early life, for which, of course, he was in no way responsible, has been his heaviest handicap. Coupled with this has been the lure of dissipation, against which fatal attraction Jackson has perhaps accomplished as much as any one else might have done placed in his shoes. It is hard for a young man fresh from a penniless life of comparative servitude in a Southern cotton mill to spring all at once into the limelight, to be feted and admired by the sharks that lurk for the unwary on the outskirts of every big, cosmopolitan city, and escape all damage from such environment. Jackson has not done so, as his declining record shows. But experience is the only school, and the lessons of one or two comparatively misspent seasons might be well earned in a renewal of ambition and brilliant service in the five or ten years that are left him.

I remember that Ed Walsh once told me that when he was fighting to make good with the White Sox, the main incentive in his work was that the shadow of the mines was on him. It was either make good or back to a life of drab, unhealthy toil in the coal fields for the man who afterward became the “spitball king.”

In Joe’s case an equally melancholy outlook is a prospective possibility. When I talked with some of his old associates at the Brandon Mills they said: “Wait five years or so. Then Joe will go through all he has made in baseball and be broke once more. What will he do? Why, he will be back in the cotton mill working for $1.25 a day.” The statement was one perhaps of jealousy or envy, but there was a grain of truth in it all the same. Joe is not naturally a spendthrift. But he has been taken advantage of in various ways and on various occasions. His business partners have robbed him; he has been mulcted of his savings. For the sake of one of the greatest players who ever trod a diamond, the warm-hearted public will wish well by Joe. For the sake of the man who started without a solitary advantage in the world and who, combating more obstacles than the average man is ever called upon to meet, has risen to the sheer pinnacle of his profession, the public will wish a better fate than a continuation of the life of poverty and obscurity from which he sprung.

The public is interested in Joe. He is a national character, a thoroughly likable — in many respects admirable — fellow of the best intentions, whose faults and weaknesses have hurt no one but himself. They are interested in and they wish all possible future success to the player who might have been — who might perhaps even yet become — the greatest player the game has ever known.